This post was written 6 months ago, but never published because I never quite felt like it was “ready.” The post is inspired by my quest over the past three years to value Bitcoin from a first principles approach. As you can see, I’m still lost.

Sometimes I tell people that I think of Bitcoin as religion. They laugh because they think I’m poking fun at Bitcoin “maximalists.” I smile so that they don’t think I’m crazy.

But I really think that you should take the idea of Bitcoin as religion very seriously. If you prefer the phrasing “ideological movement”, go with that. The point is all the same.

I used to believe that Bitcoin, in its strictest form, was doomed to fail because of its fixed money supply — which is, in my view, extremely sub-optimal. I no longer believe this. I do still believe that Bitcoin’s monetary policy is inherently flawed, but I no longer believe that this flaw guarantees it cannot proliferate.

Why did I change my mind? By taking the idea of Bitcoin as religion very seriously. I see now that Bitcoin is very much a religious/ideological movement. Religions are very real things and have real world consequences, and it is important to understand them even if you yourself are a non-believer.

Money’s Natural Ideology / Satoshi as Prophet / The Whitepaper as Sacred Text

Money is pure network effect. A collective myth in the words of Yuval Harari, or what Ben Graham calls a Class 2 truth. It matters what other people think it’s worth. In fact, it only matters what other people think it’s worth. This is the natural ideology that all money has. Such a natural ideology is attached to money—any successful money—because no money without such an ideology would ever have been successful and thus deserving of the name money. If that sounds tautological, it’s because it is. And that’s because, as I’ve said, money is a pure network effect — a Class 2 truth. People think that money is money because people think money is money. Once you fully grasp this idea, it should not be surprising at all that a large ideological movement would form around money. Money is about the spread of ideas as much as anything else.

If you follow the Bitcoin community, you will often hear Satoshi Nakamoto referred to in near-prophet status. I don’t even want to cherry pick examples here because that would be extremely unfair to those I quote. Just go and look for yourself. The fact that no one really knows who Satoshi Nakamoto is, is just perfect for perpetuating the prophet idea.

And if Satoshi is prophet, then the Bitcoin whitepaper is sacred text, and believers will want to carry that sacred text wherever they go!

But of course, there is more than just the “main” sacred text: any words ever uttered by the Prophet should be thoroughly read for direction, clarification, wisdom, and insight. And so we have The Book of Satoshi, a compilation of all of his forum posts!

I don’t know. Maybe it’s all hearsay. How pervasive is Bitcoin religiosity?

The Spread of Religions / The Spread of Viruses / The Spread of Bitcoin

Let’s say Bitcoin is indeed religious. Then we might expect it to propagate in a way similar to other religions. What can we learn from the success (and failure) of other ideologies?

Here, for example, is the early spread of Christianity (325-600AD):

You can see that early Christianity spread along trade routes — seeding at port towns around the Mediterranean.

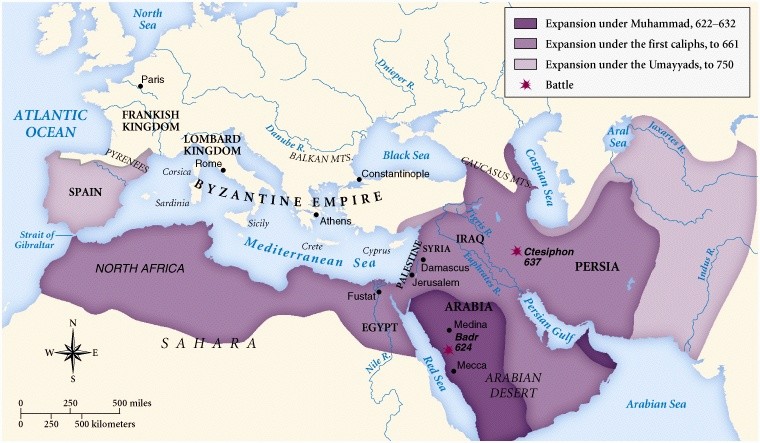

But trade routes are not the only way for religions to spread. Early Islam spread mostly through military conquest on land (622-750AD):

Here is the early spread of Buddhism (600-300BC), which also followed major trade routes:

Buddhist monks were/are very frugal which makes them very adept at travelling long journeys.

We can keep going. Here is the spread of Communism in the 20th century:

The spread of early Communism was less about trade and more about military conquest (in Europe in WW2). During the Cold War, mass media and telecommunications allowed Communism to pop up on the other side of the globe.

And for fun, here’s the spread of ebola from January 2014 to December 2015:

Now here is the spread of Bitcoin since 2013:

The map is showing locations that “accept” Bitcoin. Of course, this is all wrong. It is probably not the right way to measure the “spread” of Bitcoin — especially as a religion. But what is?

So the question remains: What does the spread of Bitcoin look like? How is it spreading? What, yes what, is the topology over which Bitcoin is spreading? This is not a rhetorical question.

Ideologies take on a life of their own. The next question is: why do successful ideologies succeed? Why do failed ideologies fail? Bitcoin is, indeed, a very powerful idea: hard money through cryptography and game theory. The politics around it are very compelling to a lot of people. Can that persist and grow?

The Great Schism / Heretical Chains / Ideology-Backed Money

Like all religions, Bitcoin has warring factions within it with opposing ideological beliefs, and these disputes eventually result in schisms.

In 2017, Bitcoin forked into two major branches: Bitcoin Core and Bitcoin Cash. (Of course, there have been Bitcoin forks before—but not like this.)

I have affectionately called this fork the Great Bitcoin Schism.

The schism revolved around exactly how Bitcoin should be scaled. Bitcoin Core has pointed to the coming of Layer 2 solutions like Lightning, while Bitcoin Cash advocated for scaling on-chain (Layer 1). Fights over what is the “real Bitcoin” ensued. I’m exhausted just talking about it.

The one important thing to understand about schisms is: they are irreversible. I cannot find one example in history where two factions reunited after a schism. This does not end in reconciliation.

Instead, you have to ask: which blockchain has the best ideology? Which branch will outlast the other? This is another serious question.

One point I will make: I get the sense that Bitcoin Cash folks are underestimating how important a strong, seductive ideology is. How can you back your pure network effect money without some sort of strong, seductive ideology?

(I have no horse in this race. Don’t message me to tell me which of Core or Cash is better. I’m not joining your religion.)

The Endurance of Institutions / Political and Social Capital / The Canonical Chain

We can’t stop there: Bitcoin isn’t spreading in a vacuum. Institutions linger.

Here is the border of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1867-1918) overlapping with the results of the 2014 presidential elections in Romania.

And here is a similar map showing the border of the Second Polish Republic (1918–1939) superimposed on the electoral results in Ukraine (south) and Lithuania (north).

Ideologies and religions are closely tied to law, politics, and institutions. It used to be, and is still true in many places today, that there was no distinguishing between the law and religion: religion is law; that’s what religion means.

So politics is a natural home for religion, and religion is a natural tool used in politics. Politics, of course, is closely tied to war. It is not surprising that many religions (and not just early Islam) spread through war and conquest, and not through mere friendly missionaries.

So of course Bitcoin has a religious component attached to it: is there a better way to create a new legal system than through a new religion? Religion has always tried to tie itself to the law; to claim itself as law. (And really, what is the law except a shared ideology of laws?)

Now, laws are housed in political institutions and a central bank is one such institution. I have always argued that a central bank has the power to create its own cryptocurrency, if it is willing, by simply enforcing a canonical chain. Enforce how? By merely making announcements. The central bank carries out 95% of its job by spending its institutional/political/social capital. There is no need for central banks to develop blockchain technology. Central banks have no business in cryptography (god help us). This here is a war of ideology, and what central banks have is the advantage of institutional, political, and social capital.

The point here is: institutions linger; they are not very liquid. Central banks are not going anywhere. Other institutions aren’t going anywhere anytime soon either. If Bitcoin fulfills its dream, there is going to have to be a struggle. Some might say a war.

This is a Serious Question

Where does this all leave us? This is a serious question. I don’t have much to offer you.

As I’ve said, I used to think that, because its monetary policy is (in my view) sub-optimal to what currently exists, Bitcoin would not proliferate very far. I now believe that these two things can be independent: Bitcoin might proliferate despite having inferior monetary policy. I mean, why not? It’s seems so obvious to me now: money is more than just monetary policy.

In the ultra long-run, this thinking might be right: civilizations with superior monetary policy should be more likely to thrive, survive, and expand. But that may take a long time and, worse, be an overly simplistic assessment for such a complex adaptive system.

If Bitcoin wins and maintains its fixed money supply, the world is going to become a much more volatile place. (Why? Because that is what central banks do: they stabilize.) And if you can predict how that plays out — that is, who wins the religious wars — you can make a lot of money.

What are the best models for predicting the spread and competition of religions? I am not making fun of Bitcoin here. I take the idea of Bitcoin as religion very seriously, and I think you should too.

To close, here are some questions worth thinking about:

- What are the best models for predicting the spread of ideas?

- What are the best ways to assess competition between ideas?

- How strong is Bitcoin’s ideology?

- How much institutional, political and social capital do central banks and other institutions really have?

- How easy/difficult would it be for a central bank to fork Bitcoin and set its own block reward monetary policy? (i.e. Do they have the social capital?)

- How sticky/entrenched is Bitcoin’s monetary policy? (Remember, it can change.)

- Are the institutions of money and law strong enough to survive in their current form? What will change and, just as important, what won’t change?

Answering these questions can tell you the future.

Addendium: The Spread of Language

Like money, the value of a language comes from its network effect: a language is only valuable if other people use it. Language, however, is not a pure network effect: a language that only you know would still be valuable for your own note taking or record keeping, for example. But, importantly, a network effect around language is much stronger than a network effect around value (i.e. money).

The spread of languages is similar to the spread of ideologies. Languages are ideas, of course, but they are not seductive, contagious, and virulent like ideologies. This means that languages travel much less easily than ideologies. Typically, languages require entire populations to migrate in order to spread (unlike ideologies which can be spread with mere missionaries). More so than ideologies, languages need a vacuum to spread, and it is very hard for a region’s dominant language to be displaced without some sort of powerful enforcement (like armies). This is also why so many isolated language dialects form, persist, and then become languages in their own right (every Romance language is just vulgar Latin). In other words, languages mutate more quickly than they spread, and become distinguishable from their mother languages (which have also mutated) by the time they reach a new destination.

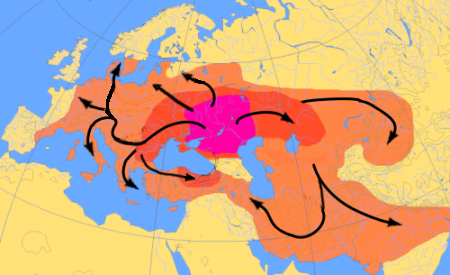

The most widely studied family of language is the Indo-European. There are several theories as to where the Indo-European mother language originated and then spread. According to the most popular theory, the Kurgan Hypothesis, the language originated in the Ukraine and spread like this (4000-1000BC):

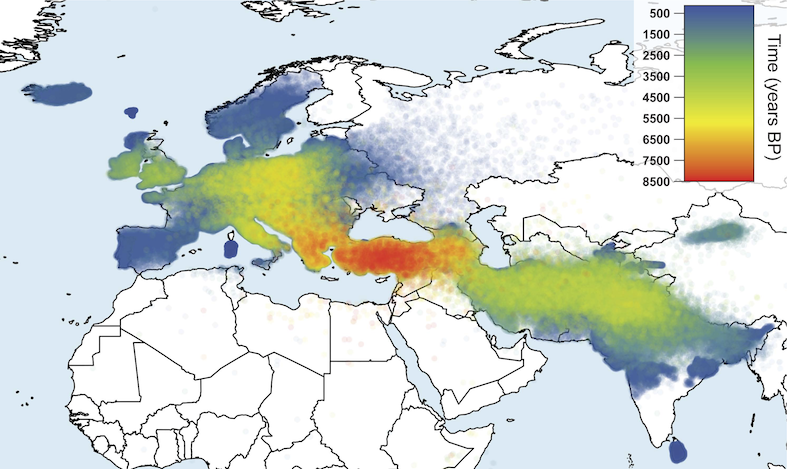

Alternatively, according to the Anatolian Hypothesis, the language originated in modern day Turkey and spread like this (8500-500BC):

(The authors of the Anatolian Hypothesis have a wonderful website with wonderful, wonderful images and animations: http://language.cs.auckland.ac.nz/. Warning: Better animations do not imply a better theory.)

I would like to point out that every theory agrees (assumes?) that the Indo-European languages spread through migration, on land. That’s important.

Which brings us back to the question: what is the topology over which Bitcoin is spreading?

Thanks for reading. Tell your friends.